Resident Program - Case of the Month

December 2022 – Presented by Dr. Luke Dang (Mentored by Drs. Kurt Schaberg and Han Lee)

Discussion

D.) Myxopapillary ependymoma (MPE) is a WHO Grade 2 ependymal neoplasm which is most characteristically located in the filum terminale/conus medullaris, and less frequently in the cervical or thoracic spine, intraventricular spaces, or brain parenchyma. However, rarely this entity can also occur in subcutaneous tissue in the sacral-coccygeal region (dorsal to sacrum or in deep soft tissue anterior to sacrum and posterior to rectum). Radiographically, MPE typically is sharply circumscribed and enhancing, and can demonstrate cystic change. The average age of presentation is in the early to mid thirties, with a male predominance (1.7:1), however a significant subset of tumors occur in pediatric patients (1/5, Sonneland et al). If resected entirely and intact, the clinical prognosis for this entity is good (OS after 11.5 years of 94%, Bagely et al), however rupture or spillage of tumor can result in dissemination via a CSF route. Tumors arising in pediatric patients demonstrate a more aggressive behavior with a higher rate of local recurrence and neural dissemination (Fassett et al). The presence of residual disease is correlated to overall survival (Abdulaziz et al).

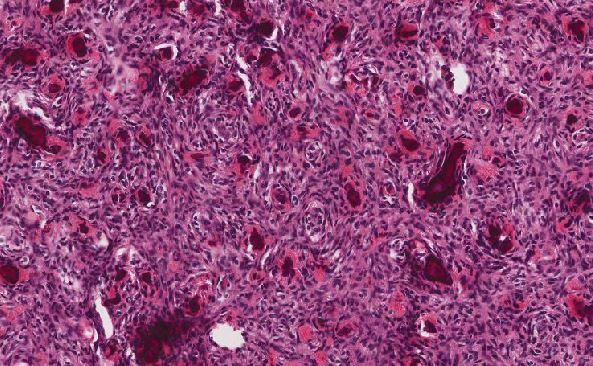

Myxopapillary ependymoma demonstrates a characteristic pseudopapillary architecture of well-differentiated columnar to cuboidal perivascular epithelial cells arranged around microcysts of mucin, accompanied by hyalinized vascular channels and myxoid matrix. The tumors are positive for GFAP and S100 (subset). Although this case contained regions which demonstrated typical morphology features and immunoprofile, in some instances MPE may contain areas which more closely resemble classic ependymomas including the presence of perivascular rosettes (mixed tumors). Cellularity may vary significantly within the tumor. Rarely, MPE may have display malignant behavior with mitotic activity (>5 per HPF, Ki-67 >10%), microvascular proliferation, and necrosis. These anaplastic variants demonstrate increased cellularity with reduced mucin. Although rare, these variants demonstrate more aggressive behavior, therefore. This entity has a distinct DNA methylation profiling, therefore this method may aid in definitive diagnosis in ambiguous cases.

The differential diagnosis includes myxoid soft tissue lesions such as myoepithelioma (EWSR1 gene rearrangement in 50% of cases, EMA or keratin positive), chordoma (keratin positive, GFAP negative, classically contains physaliphorous cells), metastatic adenocarcinoma (mucin may be present, keratin positive and GFAP negative), and extraskeletal myxoid chrondrosarcoma (negative for GFAP). GFAP positivity has been reported in myoepithelioma (parachordoma), and the chondromyxoid to hyalinized stroma can have similar appearance similar to areas of MPE lacking classic pseudopapillary architecture, therefore caution should be used in differentiating these entities (Hornick et al). In this case, although large regions of the tumor were hypocellular and evoked a wider differential, areas with a more characteristic morphologic appearance and positive GFAP and S100 staining were supportive of a diagnosis of MPE. Additionally, in this case, DNA methylation testing further supported the diagnosis.

Although MPE classically arises from the filum terminale and exhibits a pseudopapillary mucinous appearance, this case demonstrates that MPE can less frequently arise in soft tissue locations and exhibit a variably hypocellular myxoid appearance (which may cause diagnostic uncertainty particularly in the setting of biopsy due to sampling of regions without classic morphology). In this context, a wider differential with myxoid soft tissue neoplasms may be considered, and thorough immunohistochemical workup is warranted, along with utilization of DNA methylation profiling in challenging cases.

References

- Abdulaziz M, Mallory GW, Bydon M, De la Garza Ramos R, Ellis JA, Laack NN, Marsh WR, Krauss WE, Jallo G, Gokaslan ZL, Clarke MJ. Outcomes following myxopapillary ependymoma resection: the importance of capsule integrity. Neurosurg Focus. 2015 Aug;39(2):E8.

- Bagley CA, Wilson S, Kothbauer KF, Bookland MJ, Epstein F, Jallo GI. Long term outcomes following surgical resection of myxopapillary ependymomas. Neurosurg Rev. 2009 Jul;32(3):321-34; discussion 334.

- Fassett DR, Pingree J, Kestle JR. The high incidence of tumor dissemination in myxopapillary ependymoma in pediatric patients. Report of five cases and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 2005 Jan;102(1 Suppl):59-64.

- Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. Myoepithelial tumors of soft tissue: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 101 cases with evaluation of prognostic parameters. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003 Sep;27(9):1183-96.

- Jo VY, Antonescu CR, Zhang L, Dal Cin P, Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. Cutaneous syncytial myoepithelioma: clinicopathologic characterization in a series of 38 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013 May;37(5):710-8.

- Lamzabi I, Arvanitis LD, Reddy VB, Bitterman P, Gattuso P. Immunophenotype of myxopapillary ependymomas. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2013 Dec;21(6):485-9.

- Lee JC, Sharifai N, Dahiya S, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Rosenblum MK, Reis GF, Samuel D, Siongco AM, Santi M, Storm PB, Ferris SP, Bollen AW, Pekmezci M, Solomon DA, Tihan T, Perry A. Clinicopathologic features of anaplastic myxopapillary ependymomas. Brain Pathol. 2019 Jan;29(1):75-84.

- Schittenhelm J, Becker R, Capper D, Meyermann R, Iglesias-Rozas JR, Kaminsky J, Mittelbronn M. The clinico-surgico-pathological spectrum of myxopapillary ependymomas--report of four unusal cases and review of the literature. Clin Neuropathol. 2008 Jan-Feb;27(1):21-8.

- Shors SM, Jones TA, Jhaveri MD, Huckman MS. Best cases from the AFIP: myxopapillary ependymoma of the sacrum. 2006 Oct;26 Suppl 1:S111-6.

- Sonneland PR, Scheithauer BW, Onofrio BM. Myxopapillary ependymoma. A clinicopathologic and immunocytochemical study of 77 cases. Cancer. 1985 Aug 15;56(4):883-93.

Meet our Residency Program Director

Meet our Residency Program Director

LeShelle May

LeShelle May Chancellor Gary May

Chancellor Gary May